Elvis… Marilyn… Prince… there’s a handful of people out there who can be recognised by their mere silhouette alone. Bob Dylan is one such icon—the classic black and white photos of the revolutionary songwriter at his mid-60s lightning-in-a-bottle peak, with the wild hair of an unkempt labradoodle and a big pair of black sunglasses, scorched firmly into public consciousness.

From bootleg t-shirts to A Complete Unknown, the critically-acclaimed biopic starring Timothée Chalamet, this is the Dylan people think of when they think of Dylan—those dark shades an integral part of the persona, and a key item in the transformation from the Woody Guthrie-influenced folk singer of his early albums to the monochromatic rock ‘n’ roll scarecrow of the mid-60s.

Already hailed as the voice of a generation thanks to civil rights anthems like ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, by 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home the artist formerly known as Robert Zimmerman was moving beyond the purist, occasionally-backwards-facing world of folk music to a new frontier in sound.

And with a new sound came a new style, ditching the blue denim and worn-in workwear of his early years in favour of a modern stripped-back uniform which became every bit as famous as his music—black drainpipe jeans, a black suede military jacket and a pair of Ray Ban Caribbean sunglasses… even indoors. A million miles from the lavish, layered hippy gear the decade is often remembered for, this was a sharp, hard-edged get-up that perfectly matched Dylan’s relentless amphetamine-fueled wordplay and the raucous noise that backed it.

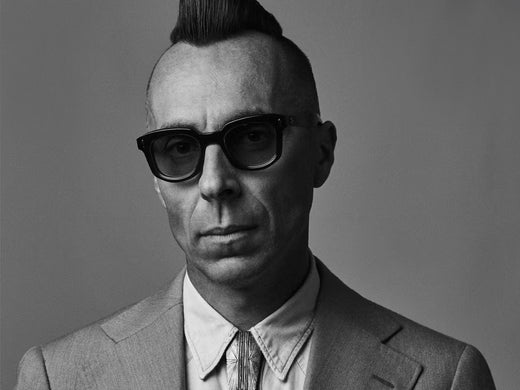

You can see the shift in D.A. Pennebaker’s handheld masterpiece Dont Look Back (apostrophes were also out the window) as a quick-witted contrarian Dylan toured England and tangled with the British press. He’d transformed from country boy to streetwise beat poet, and he had the perfect sunglasses for the job. Not only did his shades signal a new direction, but they were functional too—a vital piece of armour in the face of endless press interrogations and manic crowds. It was these shades that formed the basis for the Jacques Marie Mage Dealans—with Jerome Mage adding his signature design details to those iconic frames.

A few months later at the ‘65 Newport Folk Festival, the metamorphosis was completed, when on a whim Dylan decided to plug in a Stratocaster and ‘go eclectic’—instantly dividing fans and angering the purist folk community who felt they’d been left behind by their hero. As an aside, the infamous ‘Judas’ heckling incident of May ‘66 took place at the Manchester Free Tree Hall just a stone’s throw from Seen’s Police Street shop.

On July 29th 1966, a mere year on from Newport, Dylan’s winding ride through the ‘60s took another turn after he crashed his Triumph near his home in Woodstock. This is the subject of a lot of chatter amongst the many Dylan obsessives out there—as with no police record of the incident, the severity of the crash ranges from a minor scrape to a near-fatal dance with death. In the months that followed, Dylan disappeared from view—recovering not just from whatever injuries he’d sustained, but from the heady heights of the fame he’d been propelled into.

He didn’t tour for another eight years, and while he did still release albums, the sheer white heat intensity of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blond on Blond was replaced with the more down-at-home sound of John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline.

This was a time for life in the country, playing with his young children and strumming acoustic guitars by the log pile, and his new, low-key lifestyle was echoed in his wardrobe of casual everyday gear like breezy shirts, sta-pressed trousers and the occasional pair of prescription aviators (see the above photo of Dylan at the ‘72 Mariposa folk festival, complete with red paisley bandana for the closest he ever got to the hippy aesthetic).

Meanwhile, in London, a graphic designer named Martin Sharp was about to create one of the most iconic posters of the 1960s. As the founder of counter-culture bible Oz, the Australian artist’s skewed illustrations and LSD-soaked cartoons helped to capture the flavour of the era, and get him in a fair bit of legal trouble in the process. Keen to create a powerful cover of the seventh issue of his magazine, he settled on his hero Dylan.

Combining a stark black and white portrait of the songwriter with an intricate circular pattern spiralling out from his hair and chunky letters spelling out ‘BLOWIN IN THE MIND’ in the left lens of his iconic sunglasses, the design became one of the most popular posters of the era— reproduced endlessly and sold for the humble price of £1 at the many poster stalls and shops around the capital.

Dylan had already moved on, but his fans hadn’t—and Sharp’s depiction of Dylan as psychedelic demi-god decorated the walls of countless bedsits throughout the land. Even now, nearly 60 years (and over 30 albums) later, the image of Dylan with a pair of chunky-framed dark sunglasses hiding his eyes is still one of the most enduring images of 20th century culture.